History of Minnesotas’ Black Physicians

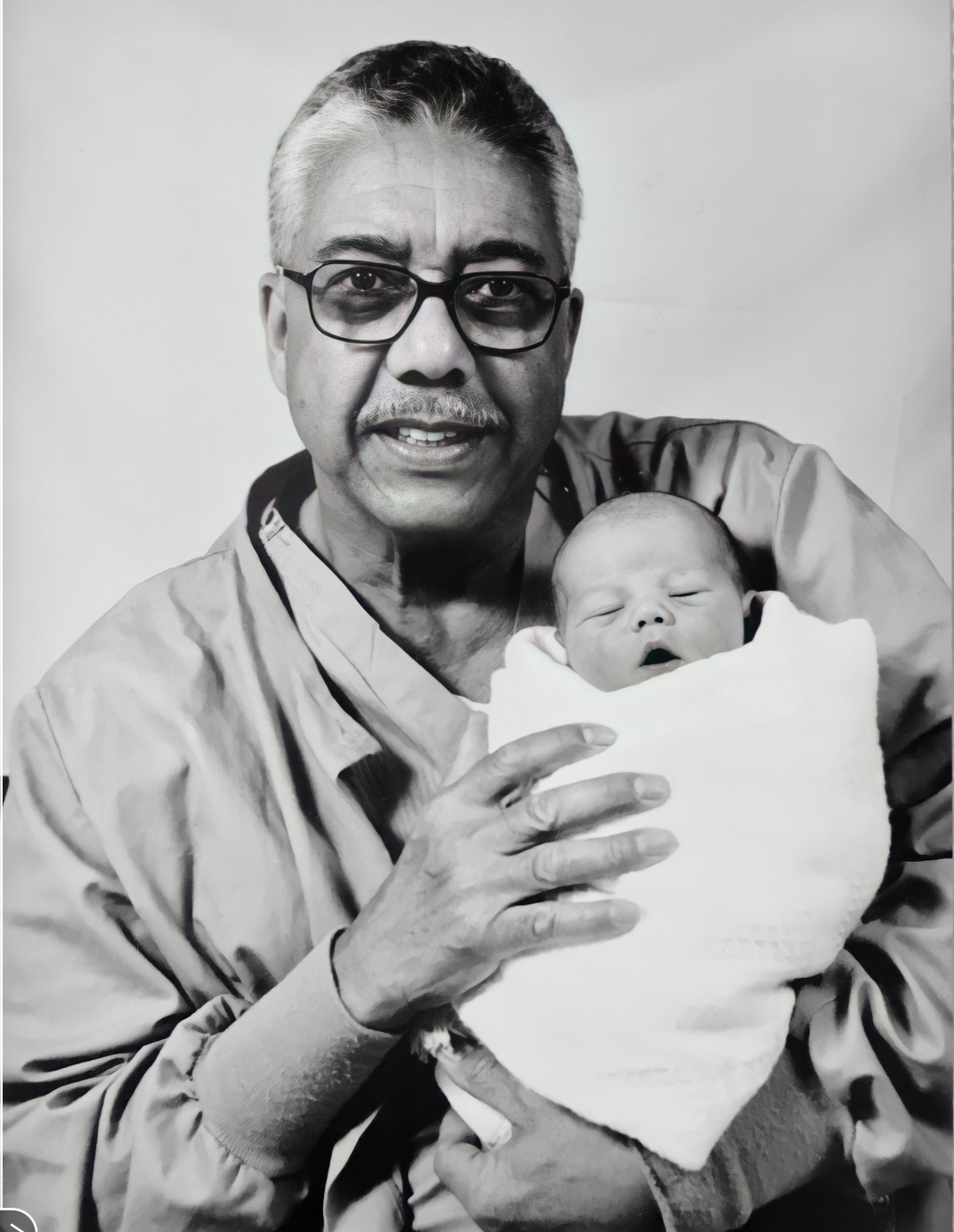

Charles E. Crutchfield Sr., M.D.

By Charles E. Crutchfield IV and Olivia Crutchfield

Dr. Charles II:

The first doctor that I heard of was Dr. W. D. Brown’s father who came here in the late 1800s and was a physician in Minneapolis. I never met him, but I met his son, Dr. W. D. Brown, a prominent family physician who took care of me and recommended medical school. Dr. Brown was about 67 when he died in about 1967 or 68. You can check on these dates later. But he was the first, one of the first black physicians in Minneapolis, and his father had preceded him.

There had been a black physician in Saint Paul in the 1920s. I don't know his name. The university might have his name. But he had an office [knock on door] on... This early physician in the 20s, and I don't know his name, was told to me by James Griffin, an old Pioneer himself who was a Pioneer system police chief. And the football field where Central plays now is James Griffin football stadium. But he told me about a black doctor who was on University Avenue in their 20s, who was a doctor for the mob. They were pretty strong here in Minneapolis and Saint Paul. And he was a mob doctor, and James Griffin probably told me about, oh, maybe 1975, that this old doctor was taken for a ride one night by the mob, and he was never seen or heard of after that.

Now, the earlier doctors that I knew here, that I interviewed before I decided to become a doctor, were in Minneapolis; Dr. Thomas Johnson, and Dr. Edward Posey, and in Saint Paul; Dr. Alexander Abrams. These were the earliest doctors.

Before Rodney England, back in the 40s and 50s in Saint Paul, we had a Dr. Crump. Everyone remembers Dr. Crump as being a good doctor but limited in certain ways because of his color, and he wore a patch over one of his eyes. Rod England came along in the 60s and stood on the shoulders of Dr. Crump, who had done a good job. And I likewise, came to stand on the shoulders of Dr. England when I came along.

When I went to med school in 1959 at the University of Minnesota, two people of color were ahead of me. There is a man from Nigeria who was a senior when I was a freshman, and there was a junior named Herman Dillard from North Minneapolis when I was a freshman medical student.

Although he really didn't practice a lot of medicine, Herman Dillard could be considered one of the Pioneers. And I don't know what happened to the Nigerian. I think he went back to Nigeria after he finished school here. But I went to med school here, was accepted in 1959, and graduated along with your grandmother, Susan; both of us started and graduated in 1963.

When I went to the Air Force during the Vietnam War, I was stationed in Spokane, Washington. And there was a dickey, a Richard Wright, from Saint Paul who graduated from med school about 68, but he never practiced here. I'm told he was an internist. He moved to Denver, Colorado.

But after about, I came back and started practice at the end of 1969, at which time Dr. Eldee[?] Troop, who would also be a Pioneer doctor, was already practicing here, whose practice started when I practiced here in the 60s. And Dr. Henry Smith, who probably started practicing Internal Medicine in Minneapolis. My guess is 60/70ish. By 1967, he would definitely be a Pioneer doctor, Henry Smith.

Charles IV:

The first question I have for you is, were you named after a family member, or does your name have a special meaning?

Dr. Charles II:

I was named after my father, Charles Crutchfield. Great people of Europe influenced him. So he added Edward. There's a King Charles of England. There's a King Edward of England. So he called, he named me Charles Edward, hoping that someday I would be someone special.

Charles IV:

Where were you born?

Dr. Charles II:

Jasper, Alabama, the county seat of Walker County, approximately 35 miles northwest of Birmingham, Alabama. I was born September 12th, 1939, at People's Hospital in Jasper, Alabama, and the delivering doctor was Dr. Pete Camp.

Charles IV:

What was your house like as a child growing up?

Dr. Charles II:

Small, but I didn't know it. I lived in the back of a barbershop. My father cut hair in the front. We had four rooms in the back of the shop that we lived in. And he had another room to make it five later on. So we had a house in the back of the barbershop; it was rather cramped. And growing up, there were the first four of us, my older sister, myself, my mother, and my father. And then, I have another brother who was born when I was about eight years old. So there were about three children and two adults; five people living in the five-room house, and it was crowded. But when you're small growing up, if you're in poverty, like we were, if you're in a crowded household, like we had, you don't realize it because you have nothing to compare it with.

Charles IV:

What was your favorite subject or teacher in school?

Dr. Charles II:

Favorite subject, biology. I had two favorites, one was Andrew Paul Howell, who was my teacher, my coach, football, baseball, basketball, mentor. He was a favorite teacher of mine.

And another favorite teacher was Clarence White, who taught me chemistry.

And actually, there's a third one, Mr. Professor Little John, who was in my band. I was in everything; I was in the band too, football, baseball, basketball, safety patrol. I was in everything going. I was the president of everything too, [our] class, president of the band, co-captain of the baseball team, and member of the other teams.

Charles IV:

What is the most important lesson that your parents taught you?

Dr. Charles II:

To be honest, tell the truth. And my father said, "Treat everyone as nice as you can as you go through life, and even if about 10% of the people were not like you." And I said, "Daddy, is that because," I was about 10 years old, "is that because I'm a negro, they won't like me?" - in those days, we were Negroes, by the way - "they won't like me because I'm a negro?" And he said, "Oh no, son, Negros won't like you either." That was a very important lesson.

He also told me that, when someone, another lesson that I've never forgotten, and I told you this too, don't ever try to convince someone when they don't want to be convinced of something. For example, I have a friend who said the Earth is flat, and he believes that, and he tried to convince me that the Earth is flat. And I realized what my father said. If someone believes something, do not waste your time trying to change them. And his statement was “a fool convinced against his will was of the same opinion still.” My father said, you can talk 'til you are blue in the face. You can talk until next year, that the Earth is round, and they'll still say, yeah, but the Earth is flat 'cause the Bible said, go preach my gospel to the four corners of the Earth, and the Bible is true, and they will believe it's fine.

So those two lessons, be as kind as you can and nice to everybody, you can't expect to win all people over and don't try to convince a fool against his will, you will waste your time.

Charles IV:

What did your friends do for fun when you were young? And did you have a best friend?

Dr. Charles II:

My best friend was Ernest Darnell. My second best friend was Bernard Davis. Third best friend was Milton Kirk.

And what we did for fun, we played ball all the time, football, baseball, and basketball. We also picked berries, and we would go fishing and swimming. Action things we did most of the time.

Charles IV:

Do you have a nickname? And how did you get that nickname?

Dr. Charles II:

No, I have no nickname. But my name was Charles Edward. There were other Charles’s, Charles Breeding, uh Charlie, Charles Clyde, but there was only one Charles Edward.

Even when I go south now, “there's Charles Edward”. In other words, your second name in Alabama was like your last name. Like you, maybe Charles Crutchfield. Well, there'll be another James Peterson in the big city, but down south, you went by the nickname, Billy Joel Williams or Robert Lee Jones; I was Charles Edward Crutchfield. Not a nickname.

Charles IV:

Did you get an allowance? How much was it? And what did you spend your money on?

Dr. Charles II:

I started working as a shine boy in a barbershop when I was six and a half years old. And I could truly say that after I was six and a half years of age, I never asked my father for a penny. I made money by shining shoes. I was always going down the railroads picking up scrap iron to sell. I will go to the junkyard to get copper and aluminum. I would dig worms for Mr. Allan Beady. I would catch minnows for him. I would pick blackberries and dewberries and sell them. And when I was 13, I went to a department store downtown, Jasper. Jasper was a county seat, by the way, where I grew up, had about 8,550 people when I grew up, of which about 2,000 were black.

But I went downtown when I was 13 because I was big physically, a good-sized boy. I was probably about 5'9" - eight or nine, and weighed about 140 pounds. And I went down to Engel's Department Store. I asked to speak to the manager, and I asked him for a job. I want a job, sweep the floor, be a janitor, and he said, "You're too young." And I said, "I'm 13 and a half." He said, "You're still too young to work." I said, "I don't think there's a law against working." And there wasn't in 1953. And I said, "Look, why don't you give me a job? If you don't like my job, fire me. I'm a good worker. I know I was a good worker; I hustled all my life, making money. I had money in the bank." And he said, "Will you come back in a couple of days? I'll let you know." I came back in a couple of days. He was a Jewish guy. He must have thought this little negro kid came here asking for a job and told me that he could fire me very forward if I didn't like his work. He gave me a job at the Fair Store, a small department store in the lower end of town. And I didn't care what they paid me; I just wanted a job after school to go sweep when I wasn't practicing football, go clean up. And you know what they paid me per hour? Make a guess. What do you think they gave an hour to work?

Charles IV:

Uhh, 6¢ an hour.

Dr. Charles II:

No, they didn't give me 6¢. They gave me 40¢ an hour. 40¢ an hour. I go in for about 3 hours, about a dollar and 20¢ a night after school. And all day Saturday they would work me, then after work on Sunday. But I've worked myself up from that to the big department store and then to the warehouse. By the time I left uh work in there at 15, I was making about 65¢ an hour, which I thought was big money.

Charles IV:

Did you ever get in trouble as a child or teenager?

Dr. Charles II:

Once perhaps. I was making some mischief, and someone threw a dog in the well, and they blamed me. Now, I'm doing things like throwing rocks on tin houses, making all kinds of noise. We went downtown and wrote "Kilroy was here" with soap marked on the windows. But someone thought I threw the dog in the well. And that's cruel. And they told my father, and he was waiting up for me. They to give me rather severe corporal punishment. But when he asked me, did I throw the dog to the well, I told the truth; I said, I would never do that. And my father thought about it for a while. And he said, "You know, son, I believe you. I've never seen you even kick a dog." I said, "No, a dog is a dumb animal. You don't treat animals mean. You treat him kindly." But he wondered what no one else had done to her that night. And I've ended up to other things about fairness downhill, and he talked, just go to bed and my mother were had to come going to be quick before he changes his mind and decide to beat you with that strap that he had for you.

So it took me two years to live that down. I want to trouble people; there goes Charles Edward; he threw that dog with the well. And it took me two years before people believed that I didn't throw the dog in the well. He didn't die, I heard. I went over to the well, [imitates dog bark], down the bottom of the well, barking. I didn't throw him in there. I think he fell in. They did get him out with a bucket or something. So he didn't die. But that was the only trouble I probably had as a kid. That was hard to live down. I keep getting out of trouble. I get it too.

I've never had a curfew. By the time I was eight years old I was going all over Jasper and everywhere else. Going down the track, going fishing, making my own fishing equipment. I would take the thread, and when I didn't have hooks, I would take a small safety pin and use it for a hook. I learned how to do everything myself. I learned how to tell time by the sun. I would draw a circle on the ground, put a stick in the middle, and see where the shadow fell to tell me what time it was. My mother and father never said you have a curfew. I know when it gets dark, you go home.

And, I guess one time, I may have been in a little bit of trouble, but I didn't know it. There was a creek that was wide enough to a place called Jackson Hole and wide enough, probably about 20 feet wide and 20 feet long, and it got down to about five feet deep. Well, I was swimming one day, and I was about 10, and we were all naked, and a white man started shooting at us with a .22. And it took about two seconds, the leaves above my head started falling in the water and I realized, pine leaves are falling, oh someone is shooting at me. So, I got out of there. Apparently, someone had been trampling this man's growing corn. Not me because I came from the east, and his corn was on the west side of the creek. And so I never even touched his corn, hadn't even gotten near it. But he was angry that these little black kids had been trampling his corn, so he started shooting. Now, as he is shooting to scare us, or what 11 about a foot and a half above your head falls on you, that bullet’s pretty close. So that was all the trouble. That was we, we, I ran, it was late, and I felt for about an hour or back and got my clothes and sneak home and then go back down that swimming for at least a month.

So other than that, I was never in any trouble that I can remember. I was mischievous at school. I got A's in most of my classes, but in those days they graded on citizenship, not conduct. They grade you every quarter – every month you got a grade. And my father called me in once and said, sit down. And he said, "I'm looking at your report card. Are you a bad kid?" I said, "No, Daddy. I go to Sunday school. I joined the church when I was six and a half and sometimes I even teach the Airfoot League." This was when I was about 14, I was in the tenth grade. So he said, "Well, why is it you get C's in Conduct and everything else you get A's and no less than a B+. What's wrong with you? Are you a bad kid?" I said, "No, I'm not bad. Well, everything that happened bad at the school…they blame me." And he said, "Well if the teacher leaves out of the room, I'll lock the door, and we'll not get back in, or if she leaves, we will all lock the window where she would get back in, there's nobody in the classroom. Well, I would start throwing tops that did all kinds of weird, pop-top, dainty, and we would just do crazy things. And everybody else started doing that and the teacher would, where they're coming from. As I would do things like that but never hurt anyone. The teachers don't know because people won't tell on me. The teacher doesn't know why, but I'm doing all the bad stuff." And my dad looked at me and said, "They don't; that's why you get C's. They don't." [laughs] So...

Charles IV:

What did you want to be when you grew up?

Dr. Charles II:

From the time I was six and a half I received a penicillin shot when it first came out, 1946. And I went from a person who was so sick with a high fever that was seeing my ceiling going onto the floor, and I realize as six and a half, the seven-year-old kid that's not happening. But I'm so sick that I'm seeing something; I see things. I realized that, so Dr. Hammond came in, and my Dad held me down while he gave me a penicillin shot that was on like a Wednesday. And Friday, I went back to school, and I thought anyone who can make someone get well that quickly, I think I want to do that. So growing up, I thought I'd like to be a doctor, but if I can't be, I'll be a football, baseball, basketball coach and science teacher, biology, chemistry or physics, or even math. All of that was my father. I love that.

Charles IV:

How did you meet your wife?

Dr. Charles II:

We went to a pre-med class meeting. I came here for my senior year. I was 15. I turned 16 my senior year, and I'd come to Minnesota from Alabama, and we had a pre-med meeting at the university for seniors who were interested in medical school. I was one of the few black kids there and I asked "Does Minnesota have a special rate for non-residential students?" Because my folks were in Alabama. Now, my future wife heard me ask this question and she thought, because I had a broad southern accent, oh my God, that little black suit, and little black boys from down south, he's probably dumbest Schmidt. Well, fast forward, a few months later, when school started, and we were going to classes. She happened to be in the chemistry class. And she said that save a little dumb board from down south of that southern accent, but the first big chemistry class that Professor Chatterton gave, when he was passing out the papers, I had to miss that day because my grandmother died and he was waving, "Where's Crutchfield? He made the highest score in the whole class. Where is he?" And my future wife realized that was me and that kid who had the broad southern accent was not dumb; he got the highest score in the class. So she arranged for a friend named David Friedman to introduce her to me and asked me if I would be her chemistry partner. And we, later on, became closer and I married her.

That's to give you a lesson. Don't ever judge someone by their color. Or if they're pretty or ugly, or about their accent. Let them prove to you who they are. Don't say, “oh he has a southern accent; he’s got to be dumb.” Let people prove who they are to you before you judge them. And don't judge anyone on one thing. It takes a multitude of things to judge a person. We all may be bad in certain ways. But, if you look at a person's character and his punctuality, how he dresses or cares about himself. After you get to know some of a person's physical attributes and mental attributes, then make your judgment. But don't make a snap judgment. "Oh God, he must be dumb because he’s not dressed well."

Charles IV:

What was your marriage proposal like?

Dr. Charles II:

I should tell you the truth on that one. I have never proposed. I've always been proposed to, that's God's truth. Why don't we get married is just what they say. Why don't we get married?

Charles IV:

Where was your wedding?

Dr. Charles II:

At the Congregational Church, 38 straight near 3rd avenue Minneapolis.

Charles IV:

What was your first car?

Dr. Charles II:

A 1953 Buick. Your grandfather gave me that car. It was another kind of old car to get back and forth to school. I didn't get that car until I was in med school. Probably 1960. It was not a Roadmaster; it was something like a Roadmaster, Buick.

Charles IV:

Where have you lived?

Dr. Charles II:

Alabama. Minneapolis. Saint Paul. Spokane, Washington. That's it.

Charles IV:

Where have you traveled?

Dr. Charles II:

I've traveled to many states in the United States. West. North. South. I have never been to the New England states. Out of the country: I've gone to Jamaica, the Virgin Islands, London, England, Paris, France, and Mexico.

Charles IV:

What is your favorite city to visit?

Dr. Charles II:

Maybe West Florida because it is so completely relaxed and laid back. I go there, thinking I won't run into people, saying, "Hi, Dr. Crutchfield." Actually, I have been down there hoping to get away from people down there. Key West Florida is still my favorite city in the United States.St. John's, Virgin Islands is also a nice place. Saint Croix and Saint John's.

Charles IV:

How do you handle stress?

Dr. Charles II:

That's a tough one. I have probably handled stress by exercising or doing something I like to do. Be that, have a steak dinner. Also having been brought up in the church when I'm under stress, I think I'll do all I can, and God has brought me so far. So, he's not going to forsake me now. So I'm going to turn it over to you (God). I've got to keep doing all that I can, but God, you got to help me, and I can truthfully say I have never let stress get me down, pray on it, and God will take it and help me with it and it usually turns out okay. But I try to help myself. But I'm not one who is under stress, even in surgery. I never lost my temper, threw things against a wall or yelled at a nurse, or anything like that. I handle stress with probably a religious approach. God didn't bring me this far to leave me now. And I've done all I can, Lord, it's in your hands, and move on to something I like to do and something I enjoy.

Charles IV:

What could you tell me that I would be surprised to learn about you?

Dr. Charles II:

I have probably done a few things that I don't really want anyone to know that I did. I don't mean hurt things but hurting anyone, but there are a few things I've done that I don't want people to know. I won't go into that. I could go into that, but not on tape.

Charles IV:

What is your dream for your children and grandchildren?

Dr. Charles II:

I want them to all be happy, successful, stay out of trouble, not be in jail and lead a normal, happy life. We all go through it once. I want all my kids to be successful and happy.

Charles IV:

What were your grandparents like?

Dr. Charles II:

I didn't know. The longevity of people now, the average person lives to be seventy-six-ish. When I came along, when my dad came along, the longevity was like 50. When I came on, the longevity was about 50ish.

Therefore, I had a grandmother, I know. I never knew my grandfather. He died before I was born. I had a grandmother on my father's side that I lived next door to. And I loved her, and I think I was her favorite grandchild.

And on my mother's side, I think I had a grandmother that didn't like me. It's strange, but I think about it, and she didn't like me because I exemplified a smart city kid and she was just the country kid ever done. If she told me I couldn't do something I'd do it anyway. "Oh, you can't go down there fishing because we don't have any fishing poles, and we don't have any inline." Well, I will make my own fishing pole to go fishing anyway. And I did a few of the smart things. She had not been used to a smart city boy like I was. I would go there with my friends. We will go hunting with our slingshots and BB guns. She would say, "Don't go over there." We go anyway. And she has accused me of coming out of her house about 50 miles from where I live and taking it over.

Now my grandfather, on the other hand, liked me. Her husband loved me. He was always kind to me and wanted me to spring. A spring is a place where I want to come upon the ground, to get some water when I was thirsty at an all-day meeting one time. And he remembered me when he was almost on his deathbed. I took your father to see him down in Auburn, Alabama. His name was famous, he was uh, Kaye Hollis. And I came, and I said, grandpa how you don't remember me. I'm sissies always more Charles. He said, "I know you are. You're the doctor from Minnesota." "Yes, sir." He said, "Remember when you were a little boy, I went down and gave you some water down in Bazemore to dip the water out of the spring with my new Stetson hat?" And I said, "Grandpa, I remember very well."

So my grandparents were... In those days, your grandparents were not that close to my grandmother. So my one grandmother on my father's side saw my grandmother on my mother's side, maybe three or four times in my life and she died at age 50ish.

And I saw my grandfather on my mother's side a few more times. But people didn't travel. If you did work in the same town, people didn't travel great distances because we didn't have cars. And if we did, uh, you did it go... Birmingham was 45 miles away, that was the big city. I think I went there three times in the 15 and a half years that I was in Jasper, so you just didn't go far from your home.

So my grandparents, from what I knew of them, were very nice people, especially my grandmother on my father's side and my grandfather on my mother's side. Laura Henderson and Kaye Hollis.

Charles IV:

What is the earliest memory that you have?

Dr. Charles II:

Earliest memory I have was when an important man was coming in on a train, and they put yellow ropes to keep people from getting, especially people of color, from getting close to the train station. And my mother was holding me, and in retrospect, I was around two and a half years old. Later on, I asked my mother and father, "What was that Gatherin?" And they said, "Oh my God, that was when Franklin Roosevelt came into town to pay respect to Walter Will Bankhead, who was a Speaker of the House in Washington. The reason it stood out for me is because I had never seen white people before. I looked out and saw these people. We were a black society. They looked like us, but they were a different color. And I thought these aren't people, but they're like people I've never seen before. There are thousands of them. I was two and a half. That's my earliest memory.

I had another early memory, and I don't know why I remember it. My mother wanted me to go across the street and be careful; I was about three and got some kerosene to put in the stove.

And the other early member I had was when my father went into the military in 1942. I was three years old, and I remember my mother was crying so much. She didn't think she’d ever see him again; to go to World War II. And a lot of people never came back from that war. And I remember my mother just crying and crying, and my Dad was going into the military. I have a lot of memories after that. I'm going to see him when he is at training and all that.

Charles IV:

Tell me about the day when your first child was born.

I had been at the hospital waiting for my wife to deliver for hours. And, I was interested in a boxing match that was coming up. I read about it while I was waiting for her labor. It was going to be Floyd Patterson, and Ingemar Johansson was going to fight. And I don't know if it was a first fight or a rematch. But I remember that I use it to occupy my time, so I didn't get too tense or too stressful over my wife being in labor. And it just seemed like it was never going to end. And finally, the nurses started running around going, "Oh my god, she's gonna deliver." And I thought, "Wow, that was quick. The last time they checked her, she was 3 cm dilated. And they told me that she has to be 10 cm to have the baby." We were there 6 to 8 hours before she got to 3, and now, 2 hours later, they're running around, screaming around saying, "She's gonna have the baby." And they told me to go wait in the waiting room, which I did. And those days, you couldn't go with your wife - that was 61 years ago.

Charles IV:

Did you have a favorite pet?

Dr. Charles II:

We had a dog growing up. And the first dog I had, was a little dog named Ben. And Ben died, got old. And after that we got a second dog, a girl named Nellie. So those were the only pets I had growing up. I think they both may have been Irish setters.

Charles IV:

What was high school like for you?

Dr. Charles II:

Fun. I enjoyed ascending to the highest rank in the class with their president, valedictorian, whatever it was. High school for me was fun. I never had to study that much, and I was always an A-student, and I was; it was fun because I could play football, baseball, basketball. I was ahead of the draw of the percussion setup of the band. I was an orator. We gave orations on stage in those days, speeches and I had won that too. And I made up a speech once. It was called Peacetime uses for Atomic Energy. Now, this is about probably seven years after the war ended. I was probably 13 or 14 years old, uh seven uh eight years after the war, again in '45. And I felt that you could harness the power of that atomic bomb and use it to power lights and fans and other things. So that was my topic, "Peacetime uses for Atomic Energy." Now, I went to the library, did some research on it, delivered the speech, and won first place in the county. But the speech, I think it was partially because it was novel, and people hadn't thought about harnessing the power of the atom before that time. But I thought it was interesting and I did.

I loved high school. I had a girlfriend from Parrish, Alabama. Uhh, she lived nine miles away and she was at the high school and I liked seeing her, liked being on all the teams. And when I was, I got my ankle broken playing football Junior year. I like the fact that the coach had mentioned him early AP, and rupee hall wanted me to sit next to him, although I got a cast on up to here and help him, coach, because I knew all the players out there playing with them. And I can tell who's getting beat up and who you should give him a rest and uh what I could see and I would sit next to the coach and help him, coach. And I appreciated that like that. It kept me involved.

Charles IV:

What colleges did you consider?

When I was in Alabama, I wanted to get a scholarship to Tuscany. And I thought about the possibilities. I may have to go to Alabama ANMI Alabama State. But I figured I guess I was conceited enough to figure they would find me and give me a scholarship. As it turned out, before I could go into my senior year, my father insisted I come up to Minneapolis and stay with my aunt. My grandmother moved up here by that time that I should come up here to get a good education, so when I came here to Minnesota, the only two colleges I thought about were the University of Minnesota, which was by far the cheapest, and I believe it was Hamline University, that was a university that was a Methodist College because by this time I'm going to I'm teaching Sunday School in the Methodist School holds a memorial Christian, Methodist Episcopal Church. I thought, well, maybe I can somehow go to these private schools. One of the colleges still exists, like, Hamline and it was a Methodist school.

I did not do a lot of college consideration. I didn't have a lot of choices. People are now at 8 to 10 colleges. I looked at what was the cheapest, which was the University of Minnesota. Uh, could I possibly get a scholarship to Hamline? So I have never known such a thing as looking at FAMU or NYU or Carlton. I didn't have that privilege. I had no money, and there were almost no scholarships in those days. Later, they never told me about it, and I didn't have any money, and my folks didn't have any money.

Charles IV:

What was college like for you?

Dr. Charles II:

Hard. I was living on 55 cents a day. I was thumbing to college many times. If I was able to thumb a ride from some of my friends from North High School. I didn't have to spend my money for a ride. I could buy a 55¢ lunch at the Baltimore lunch that consisted of a hamburger, a glass of milk that was sweet like chocolate and sugar, hash brown, and crackle candy bar as my dessert. I worked, I had to work. I worked at the Walgreen Drugstore, as a busboy dishwasher, and when I was able to get a job at the university, I got a job as an orderly at the hospital. So I had to study and work. It was not a lot of fun. If I could make it to my girlfriend's house, and I had to walk 26 blocks to get to her house back and forth, because I didn't want to wait on buses. I would rather walk than wait on buses. If I made it to her house, I knew I could get something to eat; that was an important thing when you're hungry. You make it to your girlfriend and ask if her folks had little money, and they could always give me some food. For the first three times, I went to my girlfriend, who became my wife later, went to her house, first three times that I made it to her house, they had beans like pinto beans or great northern beans. She pulled me aside, and she said, no, it looks like that's all we have, beans because every time you come over, like three weeks in a row came over one day, they had beans, beans, beans. She said we do have more food than beans to eat.

So college to me was hard work. I knew I had to get an A. I tried to take enough courses that I would be a full-time student. And I was all sort of tractor taken off course, at that, at the end of the second year, of the beginning of the third year of pre-med, I could apply to med school. So you have to guide your courses carefully, and I took a lot of guidance from my girlfriend's mother, who's a very bright lady, who helped me a lot, told me what to do, and was very instrumental in guiding me.

So college for me was working. Uh trying to get to school, work when you're at school, to go to your classes, uh work when you left school to go work at the hospital and make it fun ride back over to North Minneapolis where I lived and hope that I would not pick up by the wrong creep people thumbing at night and sometimes I was.

So it was... For me, college was not fun. It worked. But I had a goal, and I always prayed before tea chests that God would guide me.

Charles IV:

How did you decide on what medical school to attend?

Cr. Charles II: I had no choice with the University of Minnesota. I lived here. I didn't have a choice of applying anywhere else, and I believe in those days, the application was about $25. I only had $125 to spend. So I never thought about it... I could not have afforded to go anywhere. I even had to live at home for a while when I went to med school until I could get into the frat house, and I lived in the frat house of Pi Rho Sigma on campus. So I didn't have a choice of whether I was going anywhere else. I have nowhere to go and no money to go there with. So when the storm was over in school, I thought about the University of Minnesota.

Charles IV:

What was medical school like for you?

Dr. Charles II:

Again, hard. I was behind because I was a southern kid who had never gone anywhere but Jasper, Alabama. I didn't have the learning parishes for background. It was hard. I had to work at night when I was in med school. I worked the first two-plus years until the dean stopped me. I was working in research for Tsuchiya doctors; Doctor Tsuchiya was trying to learn about oxygen from algae to put a man on the moon. I also worked as an orderly at night, and I worked there till my junior year of med school because I didn't have any money until the dean called me in, and he was surprised that I was doing so well working so much. He told me to get a loan. I said I've tried that, they won't give me a loan. But my wife, by that time, her parents helped a little bit. But I was not the kind of person who never asked anybody for anything. But the dean must have pulled strings, calmed down to the medical school to the loan officer, and he told me to go back and tell him my name and ask for a loan. I said, they won't give it to me, and he said, yes, they will, you just tell him who you are. So sometime between the interview, he told me to stop working so much and study more to get to the top of the class to get a residence, which I didn't care about. I went down like he said, sure enough, they said, "What's your name?", "oh Crutchfield, come this way." I thought, "oh-oh, the assistant dean called down here, told his people to give me a loan, ask for $2,000. You always know that whatever you ask for in those days, you were going to get. They gave me $1700. And I paid it back within three years after graduation when I was a resident at __ to pay him back.

I worked hard. I tried to be as nice to people as I could, and it paid off. I did well.

Charles IV:

How did you pick your residency?

Dr. Charles II:

I picked it because I thought in 1963 that I was probably going to go back to Alabama to be a family doctor for the whole county for black people, in the county, Walker County. But I thought if I do take a specialty, I've got to do something where people will self-refer. I don't mean for this to be a racial interview, but when I came up, race was big. I could not depend on any white doctor ever referring a patient to me. I loved ear nose and throat (ENT), but I thought I'd starve. Were you going somewhere to say, "Oh, you got a polyp in your nose? Go see this black doctor Crutchfield." I thought ‘I won't; I won't make it; I'll starve’. So I had to go into a field that I thought if I treat the patient nice like my father said, treat everybody as nice as you can and do a good job, and I'm good at whatever I do, she will refer her sister, her aunt, her cousin, etc. It's a self-referral field and the only one that was that way that I knew, at that time, that I could get into that OBGYN. So I flipped a coin. No. No, I did not want to flip a coin with the top boy in the class who entered with a meeting to decide what field we were going to, and the top boy in my class says, "I don't have to flip a coin. You go... We can start on this internship where you want to start." I was number one in the class, and I already have my residents. I said, "What we have to d... Haven't we even finished med school? Did you get a residency? Uh, he did have one. So he said we could start on OBGYN. But I hadn't planned to become an obstetrician. I plan to be a family doctor.

Charles IV:

What was internship and residency training like for you?

Dr. Charles II:

I was like a sponge. I wanted to learn everything I could in med school and residency because I thought I would end up somewhere by myself with nobody referring people to me. Therefore, I've got to be able to integrate all the knowledge I have to help people. In med school, I thought I would end up going back to Jasper, Alabama. And then residency, I had ruled it out, I thought I would probably maybe go to Los Angeles, and I thought I'll be the best-trained person there. So I need to know everything.

It was hard. I worked.Again, I made 40 cents an hour as an intern. They paid us, but I worked 100 hours a week. I was always a hard worker. That's how I was able to succeed, not by being smart but by working hard.

Charles IV:

How did you choose your medical practice?

Dr. Charles II:

I didn't choose my medical practice. Dr. Joseph Goldsmith wrote me a handwritten letter when I was in the Air Force and asked me to come and join him in Saint Paul because his two partners had pulled away and he was so busy, he couldn't handle all of his business. So I joined him as an employee for 5 months. And he told me on the 1st of January of 1970, that I would be at 30% partner with him. He'd be 70%, I'd be 30, and each year that I stayed with him, I would gain another 5% of the business until I became a 50/50 partner in about 1974, I believe it was.

Charles IV:

What are some of the memorable stories from your years in medicine?

What were some memorable stories from your time in medicine?

Dr. Charles II:

Medical school? One of the most memorable times was the first day of medical school when they didn't think I belonged there. We were waiting for the instructor to come in to say, welcome to the 1959 University of Minnesota Medical School class, and a kid came over to me and said, "Hey." I looked up. He said, "Do you work here?" He thought I worked there. I thought I hadn't even started med school, don't start on the wrong foot and get these people angry at you. He probably wants you to adjust the thermostat or something, but be kind. I said, "No, I don't work here. I'm one of the incoming freshman medical students." and he glared at me. And when I received an honor 54 years later, as being one of the more outstanding alumni from the class of 1963 University of Minnesota Medical School, I wondered if that person was there to see I was one of the more outstanding students who graduated in '63. I don't remember who he was because I didn't know anyone that day. It was memorable to be asked the first day, "Do you work here?" That let me know that they thought I was out of place.

Another memorable time was when the dean called me; the first thing he said was, "Crutchfield, the boys in class like you." I thought, why would he say that? I later learned that that would be because he thought I would be ostracized. He thought the class wouldn't study with me. They wouldn't be with me. They wouldn't eat with me. That had happened in places like West Point. I didn't know that I remembered my background limited me; I come from a small mining camp, Jasper, Alabama. I didn't know what had happened at West Point years before. He did. And he was surprised that the boys liked me. I never forgot that. It took me 20 years to know what he meant.

It was memorable when I got my scholarship.

The most memorable thing that happened before I went to med school. The day I got the letter that said, "you are accepted as incoming Freshman Class University of Minnesota Med School 1959." Now that was the most jubilant time because only one out of seven people were accepted to med school, and that was the only place I applied was Minnesota. If they turned me down, hey, that was it. And they had called me in for an interview, that was important.

I also remember the football game. I played all kinds of sports. I played 4 sports as a medical student when I could. And one night, it was a big game, and I was playing safety. And I misjudged the speed of a guy who caught a ball on the other side of the field. I thought I would catch it. I ran him, and he outran me. And I was a goat because we lost a game by 7 points, and it was a mistake because everybody thought I would be able to outrun him, and he outran me because of my color. So 52 years later, at a reunion, they brought up, "Hey Charles, you remember that time you left a fox offering you when you were playing safety, and Jim House is in that quarterback pass, 28 Fox?" Well, what I didn't know, Fox was the fastest uh kid in the Upper Midwest. Even though he was a medical student, he had been a track star. And I had studied. When I got to Minnesota, all I did was study my CD you to try and catch up on what I had missed growing up in Alabama, a small black segregated, Southern school trying to catch up. So I was still a goat 52 years later. Everybody was laughing about that.

And the other jubilant part about med school was when I was paired with the number one boy in class who came to me and asked me "Charles, would you like to rotate with me on the internship at Ancker Hospital?”, which was Ramsey County's County Hospital. I thought the top one in the class was asking me to rotate with him. You stay with the same guy on an internship through 8 rotations on the rotating internship. I was very, very, very flattered that he would rotate with me and pick me to rotate with him. And he was number one. That was very jubilant. And when I got my acceptance to the internship, that was a jubilant uh happy time for me too.

There were a lot of times that I didn't want to go into that were not jubilant. I'll just pitch it that any time I missed any class in med school, the professor said, "Crutchfield, where were you? You were not in my class." They're almost mean to me. And after I got through, one of the guys that I thought picked on me a lot was in clinical medicine. And, I went to him and asked him, I said, "Why did you pick on me when I was a student like that?" And he surprised me with his answer. He says, "Because Charles, I thought you had potential." His name was Dr. Nicholas Minshia, a big Russian doctor. "Crutchfield, come here. What do you think about this pregnant lady? What do you think?" He was just saying, always pick on me. The other members of the class took up for me. It was always up to me because they thought I had a bad time because they always picked others... the professors seemed to pick on me. It looked like it to them, but if I missed a class to teach at Hamline. They didn't see my black face. So they knew I was out of the class. "Where were you?" And they jump on me about now; I always had a good excuse. Charles IV: What advice would you give to aspiring doctors of color? Dr. Charles II: I would give the same words to any aspiring doctor: be two things. One is flexible. You never know what you're going to be. If someone had told me the white at med school, I would someday deliver 9000 babies and save thousands of churchinall[?]. I would say, "No, impossible." Be flexible. You don't know which way the wind is going to blow, and you don't know what your choice is going to be. You may think you're going into med school to be a plastic surgeon, and you might end up being a pathologist. You may not like people. I may not want to be around a bunch of people. So be flexible. Don't go in with the mindset, "I'm going to be a surgeon. I want to be a pediatrician." Say I'm going to be a doctor, and I'll see which way the wind blows. So be flexible. That would be most important.

Number two, and this was a motto I had that carried me a long way, learn as much about every discipline that you possibly can by that when you're in Pediatrics, learn all about babies when you're in internal medicine for females, learn all about female internal medicine, when you're in the emergency room, learn how to do a tracheostomy, how to stop bleeding. Learn everything about every discipline that you're in, and I took that as my model because when I went to a med school, I thought that after my rotating internship, I would end up being a physician in Jasper, Alabama, and no one would refer to me. I mean, I could refer anybody out. I had to take care of everything myself. I even had to learn pathology. Now, things I learned in med school, in Pediatrics, I have used at age 80, 81, 82 on my grandkids, Amari and Cameron. He doesn't have a fever; he's not that sick. I knew that from Pediatrics. So I would say those two things, be flexible and learn as much as you can about every discipline that you go through in medicine because you never know which discipline you'll have to reach and use the knowledge you learned there and some other field. No knowledge that you learned is ever wasted. Use it as your broad base to make your decisions.

Charles IV:

What is something important that you know now that you wish your younger self knew?

Dr. Charles II:

That I was going to live this long. I probably would have taken better care of myself. I probably would have kept my weight down a little bit more than I did the last 20 years, although it's okay now. You never think about preserving your body, that someday you'll get old. And I would have probably not smoked. I smoked for 15 years. I probably would not have a drink. I drank for 40 years. I stopped drinking about 40 some years ago.And I would have probably tried to get more rest. I'd have done more to preserve my body if I had known I was going to live. If someone said, "Crutchfield, you're going to be 82." No, I wouldn't get past 50, I thought. And as it turned out, I did. So I would say, preserve your body and look upon your body as a, as a Bible says, it's your temple, take good care of it. Don't defile it with alcohol, smoking, drugs, or anything like that. This is the only body you'll have.

The other thing I tell people, take good care of your teeth. I always took care of my teeth. I have most of them now. I think I got about 29 of my original teeth in my mouth. Uh, dental health relates to longevity too. I found out later; I didn't know it was incidental.

Charles IV:

And the final question is, what makes you happy?

Dr. Charles II:

What makes me happy is knowing that my grandkids are growing up and reaping some of the rewards of my hard work back when I was 18 to 30.

Another thing that makes me happy is seeing my grandkids are growing up—no one's dead. And no one is in jail. That's a big thing for black people, not to be in jail. So, so many of us have been put in jail.

Another thing that makes me happy is knowing that I have invested wisely enough to not worry about financial problems.

Another thing that makes me happy is that there's a house that I built. This is the land that I fought for and bought three-quarters of an acre. To know that I have achieved something in life.

Another thing that makes me happy is that someone thought enough of me to put my bust on the light rail line down at Victoria University. I think my son may have been partially instrumental in that, but they told me that three different people in the community sent my name in. I was the only person whose bust is up that 3 other unrelated people sent my name in.

Another thing I'm proud of is that I delivered over 9,000 babies. I never dropped the baby, and I did over 6,000 surgeries and never lost anyone. And then, for my 50 years of practice, I never lost but one patient who died of a pulmonary embolism. And that I came out of medicine without any tails wagging behind me, no lawsuits unsettled. I'm settled and nothing that's rattling over my head like a rattler or snake, that I'm contented in my old age.

And that God has allowed me to live long enough to see my grandkids, 17 of them growing up and my five children, all having done some productive things in life.

And I'm happy that I still have the right of mind. And that I'm reasonably healthy enough to walk a couple of miles every day.

And I'm happy that I still believe in God. I have a lot of questions for him. I'm not God, but I have questions for God. Why does he let COVID-19 hit people? Things like that. But, I still believe in him even though I'm a scientist. I've seen miracles in surgery, by the way, that I witnessed. I do believe in God. I'm glad I believe in God. I've seen so many people who thought they were so bright; they didn't believe God. They felt they thought they were God. I always worked for God. I was not God; I worked for him.

That's all I have to say. I'm happy about what makes me happy.

Who am I? If you're looking at the history of Medicine in Minnesota, several women were no doctors that could be looked at. There was a Mary Stokes who's a pioneer school nurse, who got me to work at the old Open Cities, which was in those days model cities. And Mrs. Vann. They are both dead. But two people who are still living were very instrumental were Beverly Propst, she's someone you can interview. She was always an activist. And another lady who was a policeman who worked for Homeland Security made me a single time. She would put on medical programs each year and would have different doctors come. And they would be worth especially about those to observe, especially Propst. She is still verbal and smart and all that. And we're not made it the docks that they case. I forgot somebody.

So those four women. Again, two Pioneers are Mrs. Vann and Mary Stopes, but they were Pioneer black women, nurses.Her daughter is named Starr Vann, and I told her when I met her, you don't have to be a star to be in my show. She's a patient, and her mother and I were very close, but she never forgot what I said, "You don't have to be a star to be in my show." That was a song, and I guess no one ever told her that. But I said, okay, Starr, you don't have to be a star to be in my show and deliver the children. She's a nice lady. So alive. She was a head of the police department out at the airport security. But those four women also, especially the one uh Beverly Propst. She saw it more from the Minneapolis point of view.

[END]